J. William T. “Bill” Youngs, Eastern Washington University

“I Should Like to Invent Useful Machinery”[1]

John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, and Alexander von Humboldt –

Wilderness Appreciation and Practical Mechanics

Paper Presented at the John Muir Symposium at the University of the Pacific, Stockton, California, 2018

John Muir (1838-1914), Henry David Thoreau (1717-1862), and Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) are each famous naturalists. We can easily picture any one of of them in a wilderness setting: Muir beside a waterfall overlooking Yosemite, say, Thoreau contemplating Walden Pond, and Humboldt climbing high in the Andes. Each found fulfillment exploring and writing about the natural world.

And yet, if we are to understand each fully, we need to imagine them in other, quite different settings. Let your imagination roam and settle on John Muir in a factory in Indianapolis designing better ways to make buggy wheels and organize a work force. Moving back in time, we can view Henry David Thoreau at work in his family’s little factory in Concord, Massachusetts, creating fine pencils. And a few decades earlier we find Alexander von Humboldt deep in a Prussian coal mine, working as a mining inspector, and inventing devices to promote mining safety.

My interest in these three men begins with a question: how is it possible that an environmentalist such as John Muir, who early in life rejected a career among the “inventions of man” preferring instead a life among “the inventions of God,” could have been, none the less, proficient at—and even attracted to—“practical mechanics”? I intend to explore with you today some facets of Muir’s “practicality,” then by way of comparison describe these two other pioneer environmentalists, Thoreau and Humboldt, who displayed similar capacities.

John Muir

Knowing as we do today the eventual trajectory of John Muir’s life towards wilderness rambles and studies, we might imagine that–in Shakespeare’s phrase–some god had “chalked forth the way that led him thither.” Surely he was born to be “John of the Mountains” superb saunterer, incomparable author of books about the Sierra, Alaska, and other wild places; father of national parks; founder of the Sierra Club; and defender of Hetch Hetchy Valley. Muir’s narrative of his Boyhood and Youth, is one measure of this life-long inclination towards nature.

“WHEN I was a boy in Scotland,” he tells us, “I was fond of everything that was wild, and all my life I’ve been growing fonder and fonder of wild places and wild creatures…. I loved to wander in the fields to hear the birds sing, and along the seashore to gaze and wonder at the shells and seaweeds, eels and crabs…. and best of all to watch the waves in awful storms… when the sea and the sky, the waves and the clouds, were mingled together as one.”

When he was eleven years old he learned that his family would be moving to an even wilder place, America—and he was ecstatic:

“No more grammar, but boundless woods full of mysterious good things; trees full of sugar, growing in ground full of gold; hawks, eagles, pigeons, filling the sky; millions of birds’ nests, and no gamekeepers to stop us in all the wild, happy land. We were utterly, blindly glorious.”

Despite hard farm labor in America under the direction of his stern father, John Muir found that Wisconsin lived up to his expectations:

“Oh that glorious Wisconsin wilderness! Everything new and pure in the very prime of the spring when Nature’s pulses were beating highest and mysteriously keeping time with our own! Young hearts, young leaves, flowers, animals, the winds and the streams and the sparkling lake, all wildlife, gladly rejoicing together!”

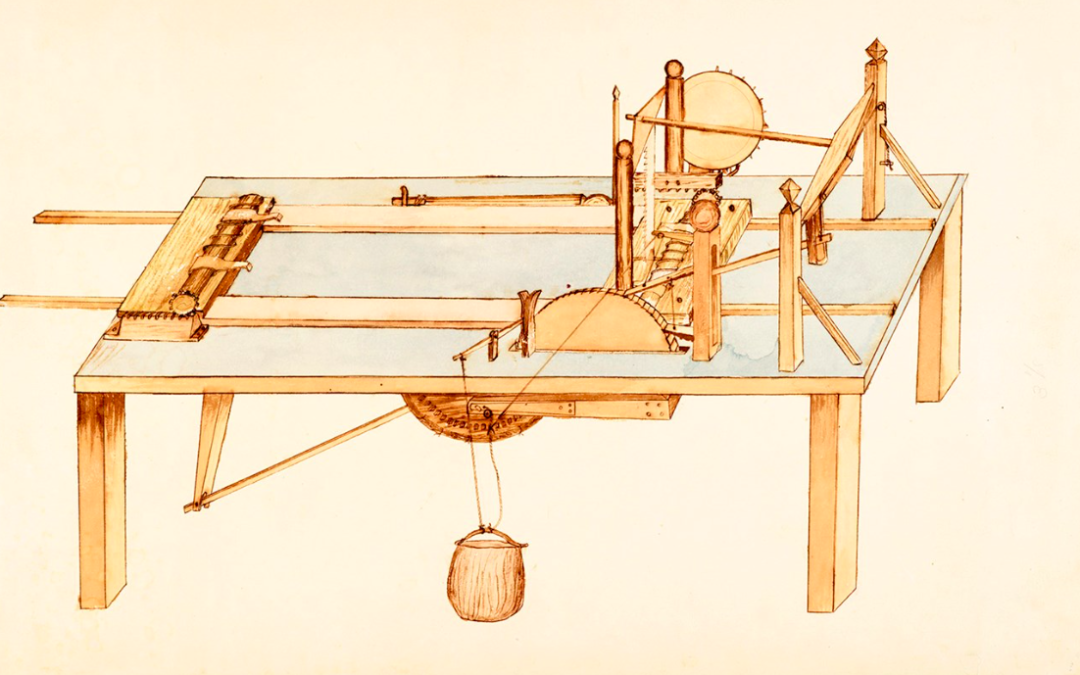

From such descriptions of John Muir’s youth, we can seemingly draw a straight line to the honored icon of American wilderness appreciation and preservation. And yet, if we could go back in time – without any knowledge of the future – and see him rise at 1:00 in the morning in his family home in Wisconsin to work on inventions that we’ve learned about at this conference, we might imagine for Muir an entirely different future. When he took his inventions to Madison to exhibit at the state fair, a newspaper praised his “ingenious specimens of mechanism.” When soon afterwards Muir moved into a dorm room at the University of Wisconsin, he took his inventions with him.

Decades later a fellow student, Harvey Reid, remembered John Muir for his genius and enthusiasm as an inventor. Reid occupied a nearby dorm room and admired Muir’s hand-made clocks and rotating bed. In an article written for Outlook about 40 years after their college days, Reid wrote of Muir:

One day he came in and announced to my roommates and myself that he had fixed his alarm so that it would waken him on pleasant, sunshiny mornings, but would allow him to sleep if it should be rainy or cloudy. Of course, we were eager to see the phenomenon, and followed him to his room for the disclosure. He had detached the little cord from the clock, and carried it through staples in the floor and up over the sill of the window, which faced the east. Where it [the cord] crossed the stone sill outside, it was replaced by a thread, under which at a convenient spot, he had rubbed powdered charcoal. Above this he had fixed a hand magnifier, or sun glass at such an angle and focus that when the sun rose it would burn the thread in two, and thus trip his bed and awaken him!

When he published his reminiscence, Harvey Reid had not seen John Muir since leaving college and assumed that, given his classmates inventiveness, Muir must have entered a career in practical mechanics. Years after leaving Madison Reid read about a western scientist who “discovered the Muir glacier” but never imagined that this could be the classmate he had known in Wisconsin. “I expected to hear of him as a great inventor or mechanical expert,” Reid noted.[i]

Back in time, several years after leaving the university John Muir did indeed appear to be entering a mechanical career path. In 1865 he went to work in a small factory making agricultural implements in Canada. During a year and a half on the job, Muir quickly improved the factory’s efficiency. In a letter to a mentor at the University of Wisconsin, he wrote:

I have been very busy of late making practical machinery. I like my work exceeding well…. I invented and put in operation a few days ago an attachment for a self-acting lathe which has increased its capacity at least one third. We are now using it to turn broom handles, and as these useful articles [brooms] may now be made cheaper, and as cleanliness is one of the cardinal virtues, I congratulate myself on having done something, like a true philanthropist, for the real good of mankind in general. What say you? I have also invented a machine for making rake teeth,… [and] still another used in making the handles,…. Farmers will be able to produce grain at a lower rate, and the poor to get more bread to eat. Here is more philanthropy, is it not? …. I am at least receiving my first lessons in practical mechanics….[ii]

In March, 1866, the factory was destroyed in fire. Muir was offered a job to help rebuild it, but instead he went to work at a factory in Indianapolis that manufactured spokes, hubs, and other parts for carriages. Once more he distinguished himself, and he quickly doubled his salary. Among his accomplishments, he invented a machine that could “automatically make wooden hubs, spokes and felloes [the outer rims of wheels] and assemble them into a fully completed wheel.” [supply note] Several of his letters at this time show a young man—almost 30 now—settling into an industrial career. In May 1866 he wrote his brother Daniel: “I have about made up my mind that it is impossible for me to escape from mechanics. I begin to see and feel that I really have some talent for invention, and I just think that I will turn all my attention that way at once….I am determined not to leave it [Indianapolis] until I have made my invention mark.” (Muir underlined the words “invention mark.”)

[John Muir to Daniel H.Muir, May 7, 1866]

Muir was by no means reticent about his factory work: in fact, he was genuinely enthusiastic about designing “useful machinery.” He wrote Jeanne Carr that he liked “the rush and roar and whirl of the factory.” But at the same time he retained an appetite for wild nature, which he fed with weekend outings into the forests surrounding Indianapolis. In letters at this time he suggested that, in effect, he did not love industry less, but nature more. He revealed this ambivalence in a letter to his sister Sarah soon after arriving in Indianapolis:

Much as I love the peace and quiet of retirement, I feel something within, some restless fires that urge me on in a way very different from my real wishes, and I suppose that I am doomed to live in some of these noisy commercial centers. Circumstances over which I have had no control almost compel me to abandon the profession of my choice, and to take up the business of an inventor, and now that I am among machines I begin to feel that I have some talent that way, and so I almost think, unless things change soon, I shall turn my whole mind into that channel.

Thus, at this stage in his life John Muir was pulled in two directions: he felt some “restless fires” drawing him towards invention, while recognizing that his “real wishes” drew him elsewhere. That “elsewhere” he described in this report on one of his excursions into the woods outside of Indianapolis: “When I first entered the woods and stood among the beautiful flowers and trees of God’s own garden, so pure and chaste and lovely, I could not help shedding tears of joy.”

[quoted in Worster, Donald. A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir (pp. 96-97). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition]

Drawn though he was to nature–”so pure and chaste and lovely”–Muir realized: “I was in great danger of becoming so successful that my botanical and geographical studies might be interrupted.” That “danger” was forestalled by a factory accident: a sharp file pierced the cornea of an eye; causing the other eye to reacted in sympathy, so that he was completely blinded. When after a month of total darkness he could see again, he paid heed to those “real wishes” and, in his words. “I bade adieu to mechanical inventions.”

Soon he was walking a thousand miles to the Gulf of Mexico, traveling on to San Francisco, and hiking to the Sierras. The call of those “real wishes” he had experienced in Indiana, would now guide him into that wilderness career for which he is so famous. But we should recognize that this avocational outcome was not inevitable. “John of the Mountains” had an abundance of talent, the possibility of a respected career path, and sufficient enthusiasm to have instead become, say, “John of the Carriage Trade.”

Henry David Thoreau

Like John Muir, Henry David Thoreau was a naturalist with a capacity for practical mechanics. Thoreau is, of course, best known for his descriptions of nature and his recognition of its natures importance to humankind. Before turning to the inventive Thoreau, let’s spend a moment with several of his most compelling statements about nature:

Of his two-years sojourn at Walden Pond he wrote: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Briefly, two others of my favorite Thorouvian quotations:

“I believe in the forest, and in the meadow, and in the night in which the corn grows.”

“Perhaps on that spring morning when Adam and Eve were driven out of Eden, Walden Pond was already in existence, and even then breaking up in a gentle spring rain accompanied with mist and a southerly wind, and covered with myriads of ducks and geese.”

We remember Henry David Thoreau for the beauty of statements such as these and also for his trenchant condemnation of wilderness wastefulness, as in this passage about loggers in the Maine woods.

When the [wood]chopper would praise a pine, he will commonly tell you that the one he cut was so big that a yoke of oxen stood on its stump; as if that were what the pine had grown for, to become the footstool of oxen. In my mind’s eye, I can see these unwieldy tame deer,… taking their stand on the stump of each giant pine in succession throughout this whole forest, and chewing their cud there, until it is nothing but an ox-pasture is left]…. Why, my dear sir, the tree might have stood on its own stump, and a great deal more comfortably and firmly than a yoke of oxen can.

One measure of Henry David Thoreau’s importance as a naturalist is the influence that he had on John Muir. Muir owned an extensive collection of Thoreau’s writings including the Journals as well as Walden, Maine Woods, and other standards. Most of Muir’s copies of Thoreau’s writings are housed right here at the University of the Pacific in the Holt Atherton Library. Muir would read the Thoreau books, making pencil marks in the margins beside passages he particularly liked, then at the back of each volume, he would his create an index, listing topics and page numbers. For example, in Thoreau’s Maine Woods, which Muir carried with him at least once to Alaska, he created an index for these terms as well as others: “camp fires,” “mountain scrambling,” “danger of falling trees,” “thunder storms,” and phrases and sentences such as: “solemn bear-haunted mountains,” and “a howling wilderness usually does not howl.”[2] Echoes of Henry David Thoreau appear throughout Muir’s works. In his writing, for example, Thoreau’s “In wildness is the preservation of the world”[3] becomes for Muir “In God’s wildness lies the hope of the world.”[4]

Like Muir Thoreau also had a genius for “practical mechanics.” His inventiveness was most apparent in his work on pencils. The Thoreau family ran a shop were Henry sometimes worked. In her new Thoreau biography Laura Dassow Walls writes: “Thanks to Henry’s improvements, for a time Thoreau pencils were the best in America, sought by artists, engineers, surveyors, architects, carpenters, and writers—everyone who depended on a good pencil.” Thoreau began by tackling a basic problem: “Why were American pencils so terrible? They functioned, more or less, but were coarse, brittle, greasy and scratchy. Leads were still made from a warm paste of ground graphite, bayberry wax, glue, and whale oil, pressed into grooves cut in slats of cedar wood, topped by a second slat, cut, and finished. But imported French Conté pencils were far superior.” Henry “made the leap” to improve American pencils. He “invented a new graphite mill, a tall churn that used airflow to sift out the finest particles, leaving the rest in the chamber for further grinding.” Later he refined that process even further and went to work on designing machinery to manufacture circular lead to replace the conventional square lead: “Thoreau dreamed all night of wheels and gears,” Walls writes.

While his most inventive work took place in the family pencil factory, we should remember that Thoreau used his mechanical ability also to build “with the labor of his hands only” this cabin at Walden Pond!

Alexander von Humboldt

The great German naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt loomed large in the thoughts of both Thoreau and Muir. Two years after leaving the University of Wisconsin, Muir wrote Jeanne Carr, “I desire to be a Humboldt.” And Thoreau once wrote: “I am especially attracted by such books of science as…. Humboldt’s ‘Aspects of Nature.’” Less well regarded today than either Thoreau or Muir, Alexander von Humboldt was, none the less, the best known naturalist of the early nineteenth century.

Like Thoreau and Muir, Humboldt was adept at both practical mechanics and the study of nature. Andrea Wulf’s recently published biography, The Invention of Nature, provides an excellent account of Humboldt’s career, and reminds us that during his lifetime Humboldt was one of the most famous men in the world. On September 19, 1869, Humboldt’s hundredth birthday was celebrated in places as far-flung as Buenes Aires, Melborne, Mexico City, Berlin, and Moscow. In New York City, streets were lined with flags and posters, thousands of Humboldt enthusiasts marched through the city, and a crowd of 25,000 gathered in Central Park to hear tributes. Humboldt’s reputation was based on an arduous exploration of the jungles, deserts, and mountain-ranges of South America (1799-1804) as well as other travels. He wrote accounts of these journeys with the skill of a scientist and the style of a poet. Fellow naturalist around the world sent him reports on natural phenomena that helped him assemble a world wide picture of what he called The Cosmos.

Before turning to Humboldt’s abilities in “practical mechanics,” I’ll summarize three facets of his contributions as naturalist: 1) his sense of the interconnectiveness of things, 2) his awareness of the harm human beings cause to their environments, and 3) his appreciation for natural beauty.

At the celebration in Boston for Humboldt’s one hundredth birthday, Louis Agassiz, the notable Swiss-American biologist and geologist delivered a tribute to Humboldt. Agassiz paid particular attention to Humboldt’s appreciation for interconnectivity: “One of the most prominent features of Humboldt’s mind,” Agazziz said, “as philosopher and student of nature, consists in the keenness with which he perceives the most remote relations of the phenomena under consideration, and the felicity with which he combines the facts, so as to draw the most comprehensive pictures…. He penetrates into the remotest recesses of space…. Our globe is reviewed in its turn. Everything is represented in its true place and relation to the whole.” (NYT)

Later in the century, Muir expressed a similar sense of the parts and the whole with these now-famous words: “When we try to pick out anything of itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.”

Given his sense of interconnections Humboldt is sometimes credited with being the first ecologist because of his observations on climate change in South America. During a journey from Caracas to the Orinoco river, he came to Lake Valencia, a beautiful but troubled landscape. The waters had been receding for a number of years leaving dry land where once there had been water. Humboldt investigated the surroundings and concluded that the lake was receding due to man-made causes: forest clearing and water draining for irrigation. He wrote:

When forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by the European planters, with an imprudent precipitation, the springs are entirely dried up, or become less abundant. The beds of the rivers, remaining dry during a part of the year, are converted into torrents, whenever great rains fall on the heights.

While best known for a scientific approach to nature, Humboldt “believed that a great part of our response to the natural world should be based on the senses and emotions,” and he wanted to excite a ‘love of nature.’ He elaborated on this love of nature in his five-volume Cosmos He begins the second volume (1847) with a long essay on “The Poetic Description of Nature.” For example, he wrote, “No description has been transmitted to us from antiquity of the eternal snow to the Alps, reddened by the evening glow or the morning dawn, of the beauty of the blue ide of the glaciers, or of the sublimity of the natural scenery.” Humboldt welcomed and encouraged modern growth of appreciation: now, he wrote, “The mind may rejoice in the inspiring power of nature.”

Like Thoreau and Muir, Humboldt while extolling the “spiritual power of beauty” had also an aptitude for bending nature to “practical” uses. In 1791 he enrolled in a mining academy at Freiberg, near Dresden. The academy taught geological theories “in the context of their practical application for mining.” Andrea Wulf tells us: “Within eight months Humboldt had completed a study programme that took others three years. Every morning he rose before sunrise and drove to one of the mines around Freiberg. He spent the next five hours in the shafts, investigating the construction of the mines, the working methods and the rocks. …. By noon he crawled out of the darkness, dusted himself clean and rushed back to the academy for seminars and lectures.”

During a five-year period in his mid-twenties (1792-1797), Humboldt served as a mining inspector in Prussia. He spent many hours deep in coal mines pondering such problems as how best to shore up the mining shafts. During these years he also inspected salt works, experimented with ways of extracting gold from other minerals, and studied the chemical properties of gasses. He invented an improved miners’ lamp and breathing apparatus. Humboldt was so engrossed in his work that at one point he wrote a friend: “I will now live entirely for practical mining and mineralogy….I am reeling with joy.” (Ursula Klein, Annals of Science)

The transition in Humboldt’s career away from “practical mining” to environmental studies was, in its way, as providential as John Muir’s encounter with the sharp file. Until his late twenties, his wealthy and domineering mother had insisted on the mining career. Then she died, leaving him a small fortune, and with it the opportunity and the funds to begin what turned out to be a life-long exploration of nature.

Conclusion: You complete this!