“We were not allowed to use the words global and warming in the same paragraph.”

A few years ago I was at a high school reunion in Indiana and had an interesting conversation with a classmate, Jan Van Wagtendonk — you already know Jan from a YouTube video I assigned a couple of weeks ago. This was during the presidency of George W. Bush, and I had heard that the bias against science was pretty strong in the White House at the time. I told Jan that I had heard that National Park personnel (and other government employees) were discouraged from discussing global warming.

Jan told me, “We were not allowed to use the words global and warming in the same paragraph” during the Bush administration.

So how do you respond to climate change in a world which denies it exists and where there are rules even against discussing it?! The answer is, of course, that it is difficult to gather data, assess threats and damages, and create and implement solutions.

So I was pleased a couple of weeks ago when I attended a conference in Great Smoky Mountains National Park with EWU colleague Larry Cebula. We were driving through the park when we turned off the road and saw this lovely view of the mountains:

This was a beautiful view, but the park told us that all was not well in the land before us. I had been unaware until recently that the National Parks are addressing climate change; and why not, given a political atmosphere that has become more respectful of science and more dedicated to identifying challenges and solutions in climate science. (I wrote those words about two years ago — alas, the pendulum has now swung back. More on this later as we explore more deeply National Parks and climate change. Note written on October 26, 2018)

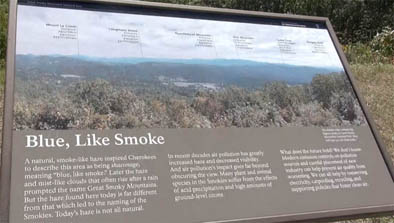

This sign is respectful but definitely “in your face” about the effects of climate change — notably air pollution — in the park:

The sign reads: “BLUE, LIKE SMOKE — A natural, smoke-like haze inspired Cherokees to describe this area as being shaconage, meaning ‘blue, like smoke.’ Later the haze and mist-like clouds that often rise after a rain prompted the name Great Smoky Mountains. But the haze found here today is far different from that which led to the naming of the Smokies. Today’s haze is not all natural. In recent decades air pollution has greatly increased haze and decreased visibility. And air pollution’s impact goes far beyond obscuring the view. Many plant and animal species in the Smokies suffer from the effects of acid precipitation and high amounts of ground-level ozone. What does the future hold? We don’t know. Modern emission controls on pollution sources and careful placement of new industry can help prevent air quality from worsening. We can all help by conserving electricity, carpooling, recycling, and supporting policies that foster clean air.”

Later that fall, I saw an even more dramatic example of the determination of the parks to face climate change problems honestly and actively. On October 18-20, 2016, I attended a two-day workshop for employees of Grand Teton National Park on the subject of climate change. I took lots of notes and made lots of films. For this post I will share with you park superintendent David Vala’s opening remarks for the conference.

For the moment the “big thing” to notice is this: In Theodore Roosevelt’s day his prescription for honoring the parks, in this case the Grand Canyon, was “Leave it as it is. You can not improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it. What you can do is to keep it for your children, your children’s children.” In that golden age before climate change, global warming, and massive pollution, “leaving it as it is” consisted mainly of keeping mining, and timber extraction, and tacky tourist traps out of the parks. No one had to think much about the threats to the parks from activities outside the immediate boundaries, to say nothing of human-caused climate change fostered by industry half a world away. But not so now!

Grant Teton National Park Superintendent David Vela

Introduction to Climate Friendly Parks Workshop, Jackson Hole, Wyoming

October 18, 2016

Superintendent Vala delivered those words two years ago. [This was written in 2018.] Would he be able to embrace the science of climate change so openly and honestly today? I wonder. Last year (2017) the new Interior Secretary, Ryan Zinke, famously “dressed down” the Superintendent of Joshua Tree National Park because he and other park staffers posted Tweets on climate change. And in various ways, including outright “climate change denial” the Trump administration has discouraged scientific exploration of climate change — no more climate change link on the White House web site for example, and NASA was told to cut back on climate change research. On the other hand I just did a “climate change” search on the National Park Service web pages, and the topic is still there with some recent posts.

Going forward with our class, let’s share any information we find on this topic, especially as it applies to the National Parks.