When I was growing up in Indiana, we used to joke that the mosquitos were so thick that they not only stole the food from the picnic table, but they flew away with the table itself! Now that was a bare-faced lie, but it grew out of the fact that swarms of mosquitos were not uncommon.

In contrast, we in Washington have it better, and I have to chuckle when a friend complains about the mosquitos when hardly a half dozen are in sight.

Recently, I have read several stories about mosquito armadas in Alaska that were nothing short of terrifying. With my students I am working on an anthology of original narratives written in Alaska before and during the Klondike Gold Rush. In 1883, just sixteen years after the United States bought Alaska from Russia, Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka of the United States Army led an expedition to explore the Yukon River from its headwaters to the Arctic Ocean. He and his men built a raft and floated 1300 miles on what was then the longest raft journey in history. Along the way they had many glorious adventures and saw many beautiful sites. But less pleasant to recount, they also suffered many tortuous encounters with mosquitos.

Schwatka sprinkled remarks on the mosquitos throughout his narrative, and then finally — driven by desperation — he gives us one of the best-written accounts to be found anywhere of the horror of mosquito multitudes. Here is his report with passages I have bolded for emphasis. Schwatka writes:

The day we walked over the trail on the eastern side of the cañon and rapids was one of the hottest and most insufferable I ever experienced, and every time we sat down it was only to have “a regular down-east fog” of mosquitoes come buzzing around, and the steady swaying of arms and the constant slapping of the face was an exercise fully as vigorous as that of traveling. Our only safe plan was to walk along brandishing a great handful of evergreens from shoulder to shoulder. As we advanced the mosquitoes invariably kept the same distance ahead, as if they had not the remotest idea we were coming toward them. An occasional vicious reach forward through the mass with the evergreens would have about as much effect in removing them as it would in dispersing the same amount of fog, for it seemed as if they could dodge a streak of lightning. Nothing was better than a good strong wind in one’s face, and as one emerged from the brush or timber it was simply delicious to feel the cool breeze on one’s peppered face and to see the rascals disappear. Our backs, however, were even then spotted with them, still crawling along and testing every thread in one’s coat to see if they could not find a thin hole where they might bore through. Once in the breeze, it was comical to turn around slowly and see their efforts to keep under the lee of one’s hunting shirt, as one by one they lose their hold and are wafted away in the wind. If these pests had been almost unbearable before, they now became simply fiendish while we were repairing our raft; nothing could be done unless a wind was blowing or unless we stood in a smoke from the resinous pine or spruce so thick that the eyes remained in an acute state of inflammation. Mosquito netting over the hat was not an infallible remedy and was greatly in the way when at work.

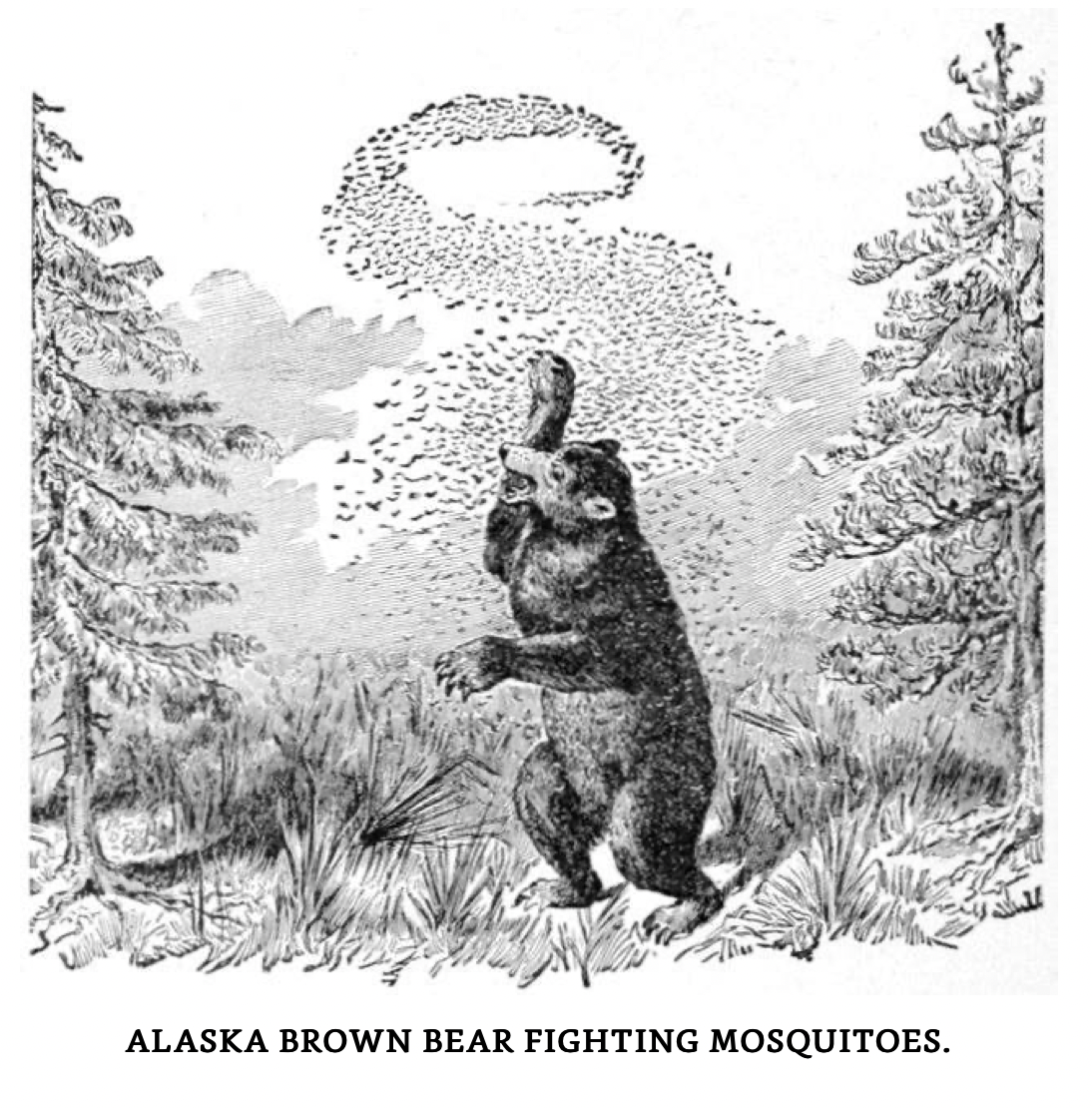

A fair wind one day made me think it possible to take a hunt inland, but, to my disgust, it died down after I had proceeded two or three miles, and my fight back to camp with the mosquitoes I shall always remember as one of the salient points of my life. It seemed as if there was an upward rain of insects from the grass that became a deluge over marshy tracts, and more than half the ground was marshy. Of course not a sign of any game was seen except a few old tracks; and the tracks of an animal are about the only part of it that could exist here in the mosquito season, which lasts from the time the snow is half off the ground until the first severe frost, a period of some three or four months. During that time every living creature that can leave the valleys ascends the mountains, closely following the snow-line, and even there peace is not completely attained, the exposure to the winds being of far more benefit than the coolness due to the altitude, while the mosquitoes are left undisputed masters of the valleys, except for a few straggling animals on their way from one range of mountains to the other. Had there been any game, and had I obtained a fair shot, I honestly doubt if I could have secured it owing to these pests, not altogether on account of their ravenous attacks upon my face, and especially the eyes, but for the reason that they were absolutely so dense that it was impossible to see clearly through the mass in taking aim. When I got back to camp I was thoroughly exhausted with my incessant fight and completely out of breath, which I had to regain as best I could in a stifling smoke from dry resinous pine knots. A traveler who had spent a summer on the Lower Yukon, where I did not find the pests so bad on my journey as on the upper river, was of opinion that a nervous person without a mask would soon be killed by nervous prostration, unless he were to take refuge in mid-stream. I know that the native dogs are killed by the mosquitoes under certain circumstances, and I heard reports, which I believe to be well founded, both from Indians and trustworthy white persons, that the great brown bear—erroneously but commonly called the grizzly—of these regions is at times compelled to succumb to these insects. The statement seems almost preposterous, but the explanation is comparatively simple. Bruin having exhausted all the roots and berries on one mountain, or finding them scarce, thinks he will cross the valley to another range, or perhaps it is the odor of salmon washed up along the river’s banks that attracts him. Covered with a heavy fur on his body, his eyes, nose and ears are the vulnerable points for mosquitoes, and here of course they congregate in the greatest numbers. At last when he reaches a swampy stretch they rise in myriads until his forepaws are kept so busy as he strives to keep his eyes clear of them that he can not walk, whereupon he becomes enraged, and bear-like, rises on his haunches to fight. It is now a mere question of time until the bear’s eyes become so swollen from innumerable bites as to render him perfectly blind, when he wanders helplessly about until he gets mired in the marsh, and so starves to death.”

Excerpt From: Frederick Schwatka. “Along Alaska’s Great River / A Popular Account of the Travels of an Alaska Exploring Expedition along the Great Yukon River, from Its Source to Its Mouth, in the British North-West Territory, and in the Territory of Alaska.” Apple Books.

Upon rereading this passage I am impressed with how well it is written. It almost makes you want to check yourself to make certain than none of these pestiferous critters is nearby! Schwatka’s writing is great, but wait, there’s more. While rafting down the Yukon and writing a journal, he also drew some wonderful sketches of the things he saw. Including…none other than that poor enrages bear. Here is his picture of Mr. Bruin: