George Meléndez Wright, Essays

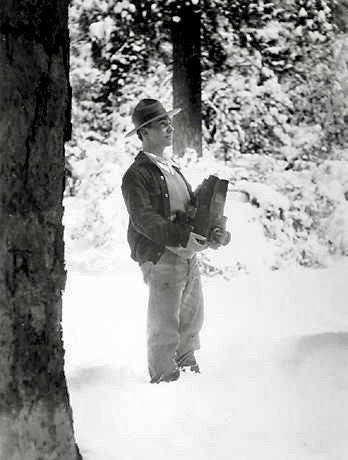

George Wright with Camera in Yosemite, 1929

How shall man and beast be reconciled in conflicts and disturbances which inevitably arise when both occupy the same general area concurrently?

George Meléndez Wright asks this question in the first essay of Wildlife Management in the National Parks (1934), Part II of “The Fauna Series,” which explored the place of wildlife in the parks. Wright is arguably one of the half-dozen most influential figures in the entire history of National Parks. Before he began his important but tragically short career, careful inventories of park wildlife were virtually non-existent. All too often, park animals were trivialized: as in feeding bears from cars, or villainized as threats to human beings and other animals. Wolves and cougars, for example, were hunted to the brink of extinction. Enter George Wright: during the 1920s and early 1930s he argued that park wildlife should be systematically inventoried and that policies should be implemented to “reconcile’ conflicts and disturbances between animals and humans.

Wright, who was born in 1904, studied Forestry and Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley. He entered the National Park Service in 1927 and soon persuaded the service to allow him to undertake a survey of wildlife and in the parks. Independently wealthy, Wright funded his own salary and that of two assistants. He and his colleagues published a number of reports, and in 1933, he became head of the new Wildlife Division of the Park Service. Unfortunately, one year later he was killed in a car crash. During the years following his death, the Wildlife Division languished, losing most of its personnel.

But today, thanks in no small part to Wright’s influence, wildlife management is deeply embedded in the DNA of the National Park Service. His lucid prose and brilliant policy suggestions are as relevant today as at any time in the past. What follows are three sample essays from Wright’s Fauna II.

Fauna of the National Parks

of the United States, Series II

MEN AND BIRDS IN JOINT OCCUPATION OF

NATIONAL PARKS

By GEORGE M. WRIGHT

How shall man and beast be reconciled in conflicts and disturbances which inevitably arise when both occupy the same general area concurrently? As man is at once poser of the question, arbiter in the arguments, and, above all, himself the executioner, his verdict will be determined directly by the use or uses he wants to make of any particular area and the order in importance to him of those uses.

Joint Occupancy

Summary: Humans and wildlife are often at odds when it comes to occupying the same places, and one mindset is that the only way to protect the interests of both is to keep them separate. The idea behind National Parks, however, is a contradiction to this and is an example of proposed land use by both man and wildlife without harm done to the other.

Whatever the designated use of an area, the desired relationships between human and animal occupants are difficult to establish. I believe from observations to date that it is justifiable to state the general proposition that the more man desires to preserve the native biota, the more complex become his problems in joint occupancy.

The opposite extremes would appear at first thought to be exemplified in the business district of a large city and a site that is set aside as a primitive reserve. In the crowded downtown district, nearly all vertebrate wildlife disappears. If one of the surviving species causes inconvenience to any ponderable group of the inhabitants, the prime objective of land use for that site automatically dictates that this species, too, must go.

In the instance of a true primitive area, man’s estimate of the greatest values to be obtained from the sum total of resources on that area—and by that I mean values for himself, of course, there being no other standard—dictates that he shall impose such restraint upon himself as to shun the area entirely or almost entirely. Because man here, in choosing to forego his share in joint tenancy of the land, side-steps the problem entirely, this is not an adequate example.

Turning to the national parks, we find ideally exemplified the extreme case for which we are seeking, for here the law specifying land use permits neither the impairment of primitive wildlife nor the restriction of human occupancy. At one bold stroke, man has assumed the whole difficult problem in its most complex form, not really as a problem at all, but as a thing accomplished—and all this by high governmental decree.

Section I of the act of August 25, 1916, to establish a National Park Service says, in part:

The Service thus established shall promote and regulate the use of the Federal areas known as national parks, monuments, and reservations, hereinafter specified, by such means and measures as conform to the fundamental purposes of the said parks, monuments, and reservations, which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.

Countless times it has been pointed out that here was an inconsistency in a first premise; that a lion and a fawn were being asked to share the same bed in amnesty; that ice and fire were expected to consort together without change of complexion; in short, that the vast American public should be brought to the parks for a vacation without disturbance of the pristine loveliness of these sacred areas. A modern Portia, this lawgiver:

Therefore prepare thee to cut off the flesh. Shed thou no blood; nor cut thou no less, nor more, but just a pound of flesh.

The National Park Service, springing into being with a thousand exigencies to meet and no time to gaze at the mountain and resolve paradoxes, accepted its charge in the spirit of a Casabianca ready to die for an impossible order. Latterly, however, it has lifted a determined hand to shape a course that will accomplish the seemingly impossible. For, after all, the history of civilization all along the way has been a record of that done today which seemed improbable yesterday, impossible the day before, and not even to be imagined in fools’ dreams the day before that.

And so now we find man and animal in joint occupation of the national parks, each armed with his full guarantee of rights. How shall both be reconciled in the resulting conflicts? Where mammals are concerned, the relationships are so ramified and complex as to give pause to the most optimistic worker. Relations between men and birds in a national park, however, are so much simpler that this aspect of the picture is really bright with promise. Some idea of what the problems of birds and men in competition in the national parks are—what is being done to meet them, and what the ornithologist may hope for the future in these last stands of the primitive American wilderness—may be gleaned from the following short accounts of problems that have already developed or are anticipated.

Categories of Problems: Birds as Adversaries to Man’s Interests

Summary: Various challenges arise in meeting the noble goal of National Parks maintaining peace between humans and wildlife. Here, Wright outlines three core issues in which man and animal come into conflict with each other. First is an example of how birds take away from the fishing activities that visitors to the parks seek out for enjoyment.

First may be mentioned those situations in which birds are offenders. To date these are few and they should never be numerous or difficult of solution. The reveilles of California woodpeckers have at times rudely awakened guests of the Ahwahnee Hotel in Yosemite, and the resulting complaints were once sufficient occasion for the death sentence. Needless to say, this practice soon stopped. Again in Yosemite, campers’ fare left on tables is frequently eaten or spoiled by western tanagers or Steller jays. It may tax the reader’s patience to have such trivial matters classed as problems at all, yet it is amazing how many persons will come to sob on a ranger’s shoulder begging for justice in the name of omnipotent “Uncle Sam” and the National Park Service, to wreak stern vengeance on some small feathered “nuisance”.

There is one type of complaint against birds in the role of adversaries to man’s interests that merits serious consideration. This occurs wherever birds are predatory upon game fish. In Yellowstone, a colony of white pelicans numbering approximately 300 birds live upon the spotted trout of Yellowstone Lake and adjacent waters during the breeding season. In many parks, notably Glacier, Yellowstone, and even Sequoia, American or red-breasted mergansers have been objects of condemnation. In Yosemite, kingfishers have raided the fish hatchery. There are other instances and certainly many more species of birds, including the beloved water ouzel, that take a toll of game fish, but the ones mentioned seem to be chosen targets for the shafts of the fishing fraternity. The reason why, in the opinion of some persons, fish predators as a group stand alone in being inimical to man’s interests is obviously that fish constitute the only crop which man harvests in a national park.

The fair principle of give and take shows the way to a satisfactory solution to problems of this type. In return for the special privilege which is his in being permitted to take fish in park waters when the hunter is denied, and even the flower lover must not touch, and also in compensation for robbing the fish eaters of their normal food supply, the fisherman must be content to restock the stream for the benefit of all. This general policy has been adopted by the Service. In cases of unusually heavy losses, such as occur where a bird or family of birds systematically raids a rearing pond, special protective measures can be devised, or, as a last resort, the individual offender killed, still without altering the status of that species within the park.

Categories of Problems: Negative Human Influence on Bird Life

Summary: Measures that are taken to increase man’s enjoyment of wildlife, can often have adverse effects on the animals that populate the area. One example involves getting rid of mosquitoes using crude oil on the water, which in turn harms the birds who occupy those same spaces.

In a second category among the conflicting interests of occupation are those in which the park residents and visitors exert an adverse influence upon the bird life. Here we find a more imposing list of disturbances already occurring, with the possibility of others to come. Man with good cause finds it essential to his enjoyment of certain of the parks to employ mosquito-abatement measures. The only effective yet economical method so far developed is to spread crude oil over stagnant waters. In Yosemite, a considerable annual toll of bird lives, notably robins and blackbirds, is the price paid, not to mention possible loss of habitats important to some species, and impairment of aesthetic values. The loss of bird life could conceivably reach serious proportions in some of the newer park projects, should either draining or crude oil application be the methods used. When the Florida Everglades project is realized, either the visitor will have to bear the discomfort of mosquitoes or leave the swamps to the birds. Elsewhere the birds must pay the price, unless some innocuous and practicable method of mosquito abatement is invented.

In Yosemite, in 1928, several band-tailed pigeons died from taking poisoned grain set out for rock squirrels around the Government barns. This type of difficulty already has been eliminated for all time, since the use of poison is now definitely prohibited within all parks, barring some emergency such as a rodent-carried epidemic of human disease.

Destruction of birds by moving vehicles fortunately occurs but in small degree, though occasionally owls and nighthawks meet death in this way, and at least one golden eagle in Yosemite was doomed as the result of striking a car radiator when frightened from the carcass of a deer which itself was an earlier victim of a highway accident. It may develop in the future that some rare and slow-moving bird will have its status definitely impaired by losses occurring in this way. In the mammal world there is the striking example of the gray squirrel colony near the foot of El Capitan. This was apparently the only remaining colony in Yosemite Valley after the great epidemic of 1920, and for a number of years practically all of the potential increase was accounted for as automobile fatalities. Then there is always the possibility of birds flying into wires. No specific instances where this has occurred within a national park to the detriment of any one species comes to mind, but under certain conditions such a complication may arise.

In desert parks, such as the new Death Valley Monument, where the water from a single spring may be vital to a part of the bird life of many square miles, and where developments to accommodate the influx of thousands of tourists may either preempt or obstruct the original availability of such water, the avian as well as the mammalian fauna will suffer. A little forethought in conserving the water to make it available at places removed from too much disturbance should successfully preserve values which might otherwise be lost.

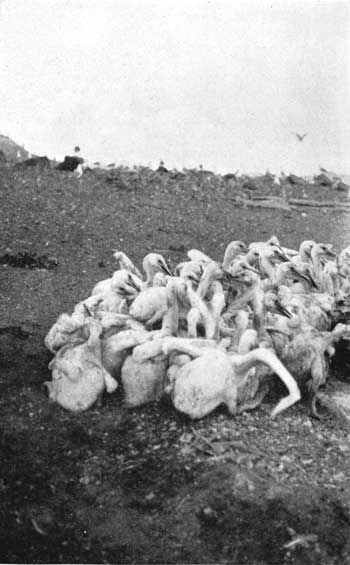

There are two classes of birds which are unable to tolerate man’s presence, at least insofar as joint occupancy of their breeding grounds is concerned. These are colony-nesting birds and large ground-nesting birds. The white pelican is a striking example of the former. Trespass on a breeding island, if permitted to any extent, may have any one of the following effects: Driving the birds off in the heat of the day may result in the cooking of the eggs. Prolonged absence from the nests during cold weather or at night will allow chilling of the eggs, with consequent destruction of the embryos. While the parent birds are off, gulls may eat the eggs. Young pelicans congregate in pods; if frightened they trample each other in the rush to escape, with many resultant deaths and injuries. If the nesting island is disturbed too frequently, the colony may desert and never return.

Figure 1. – While the parent birds are off . . .

(Photographed by George F. Baggley, Molly Islands, Yellowstone National Park, June 4, 1932.)

Figure 2. – . . . gulls may eat the eggs.

(Photographed by George F. Baggley, Molly Island, Yellowstone National Park, June 4, 1932.)

Figure 3. – Young pelicans congregate in “pods”; if frightened they trample each other in the rush to escape, with many resultant deaths and injuries.

(Photograph taken July 13, 1932, at Molly Island, Yellowstone. Wildlife Division No. 2459.)

The sandhill crane is an example among large ground-nesting birds. These birds are so shy that the constant presence of people, such as fishermen tramping back and forth, often causes them to abandon the locality or fail to bring off their young. Only two eggs are laid, and even the sudden rising of the brooding bird when frightened may cause an egg to be kicked out of the nest.

How the difficult relationships involved between park visitors and birds of the two classes mentioned above are being resolved in the minds of students of park wildlife problems is seen in the following excerpts from the report of Frederick Law Olmstead and William P. Wharton on the Florida Everglades proposed park:

It is essential that the rookeries be protected from intrusion, be made inviolate sanctuaries for the birds; but experience along the trial has demonstrated that with prevention of shooting and with entirely practicable regulation of public behavior, great numbers of people can be given opportunity to enjoy the sight of amazing throngs of birds at some of their great feeding grounds, and we believe that it will be safely practicable to admit large numbers of people to observation places so related to the rookeries that the still more amazing concentrated flights of homing birds at sunset will pass over them as they return from the feeding grounds.

Where these observation places can best be located and how arranged, how people can best approach them, in what cases by automobile and in what cases by boat, and in general how it can be made possible for large numbers of park visitors to get these and other enjoyments offered by this region, and peculiar to it, without serious defacement of the landscape by artificial elements and also (what is here even more important) without upsetting the extraordinarily intricate and unstable ecological adjustments upon which the whole character of the region depends, is a problem that requires prolonged and intensive study from many points of view by the most competent people—botanists, zoologists, and geologists, as well as engineers and landscape architects. We are satisfied that it can be solved, and well solved; but we cannot too strongly urge caution, thorough study, and patience in the formulating of comprehensive and far-seeing plans before any physical changes, however innocent in seeming, are undertaken.

Categories of Problems: Man’s Compromised Enjoyment of Wildlife Values

Summary: Enjoying wildlife is one of the elements of the wilderness that humans seek out. However, in order to keep this wildlife protected and safe, it often involves removing them from where they are easily accessed by humans. How can people appreciate wilderness if their encroachment leads wildlife to flee out of sight?

A third category of problems in securing the desired values from joint occupancy comprises the numerous situations in which man’s presence operates inimically to his own enjoyment of wildlife values. The relationship sought is one in which the greatest amount of native bird life will be readily accessible to the largest number of visitors over a maximum period of their stay. It becomes evident that birds around development centers and along roads and trails have a much higher use value than those located in spots remote and inaccessible. Thus, while the totality of bird life within the park may not be affected thereby, the clean-up practiced around centers of human occupation and along roads and as recommended for trails as well, will tend to remove certain species from the very localities where there are the maximum opportunities to see them.

Standing trees that are decrepit may have the dead wood pruned or be felled, and dead trees are commonly removed from the vicinities of buildings, camps, parking areas, and roads, partly in the interests of safety as they are potential windthrows, partly as a preventive fire protection measure, partly, perhaps, to augment firewood supply, and very largely, it may be suspected, to satisfy a psychological craving. Tidying up is so personally gratifying, and a tidy park labels an efficient administration. In justice, too, to the one who earnestly tries to please his public, the sensibilities of the city dweller, educated to the concept that a park laid out in the city style is the ultimate in park perfection, must be mentioned as a potent influence.

Yet one standing snag may be worth more than ten or a hundred living trees in supplying the peculiar habitat requirements of certain bird species. In the national parks of California, screech owlpecs, saw-whet owls, pygmy owls, hairy woodpeckers, willow woodpeckers, white-headed woodpeckers, pileated woodpeckers, California woodpeckers, red-shafted flickers, tree and violet-green swallows, red-breasted nuthatches, western and mountain bluebirds, and mountain chickadees are some of the birds that may be affected by this loss of nesting sites and food supply. Crowns bare of foliage are veritable baits for the slower hawks, vultures, band-tailed pigeons, and other birds. If the concentration of these birds becomes less along the beaten paths, it is of little avail that they may be more common in the far places. Even the most energetic hikers perforce spend much of their time in camp, and by far the majority of total visitors checked in at the entrance gates never leave the highways and the places where they stop at night.

Nor is this all. There could be recounted an even longer list of birds, this time among the ground- and bush-inhabiting forms, which become increasingly scarce in the very places where people are most apt to see them, in proportion to the effectiveness of clean-up of downed and rotten logs and of brush piles and litter. Whereas lack of facilities to carry clean-up along roadsides to a logical finish has operated to the benefit of the fauna in the past and hence to the benefit of man in the enjoyment of the park, the future may tell a very different story.

Drying up of reservoirs for bird life not only occurs as a by product of clean-up work. The trampling by thousands of human feet in congested areas destroys the habitat of grassland birds; and so the adverse influences multiply. It will be argued that development areas may, on the other hand, favor an increase of bird life. With many important reservations, this is true, particularly of the public camps. Yet the species favored are usually those aggressive forms so well represented by the members of the jay tribe, whose presence in unusual numbers will, in turn, cause smaller birds to seek a more peaceful life elsewhere.

But this leads out of the field of direct influences of human and bird populations upon one another into the multifold complexities of indirect influences. Research has as yet uncovered next to nothing in this virgin exploring ground, and we cannot even guess what trends in wildlife administration for national parks will be indicated when at last the factual basis shall be spread before us.

Hope is Not Lost

Summary: Even though these issues may not be solved yet, the recognition that they exist is the first and biggest step. Wright has high hopes that the conflicts between man and wildlife will be resolved, allowing the National Park philosophy to fulfill itself.

In review of the foregoing facts and postulations, it is the writer’s opinion that the first two categories of problems arising out of joint occupancy (namely, those in which man affects the birds adversely and those in which this order is reversed) include but a few maladjustments and that these will be resolved successfully. The third category, covering those relationships in which man’s presence operates to the detriment of man’s use of the wildlife values, presents many more difficult problems; but their solution is by no means hopeless. A widespread appreciation that the problem exists is the first and most important step. This is already being realized, and the foundations of approach and practice, too, are in the mixer.

Can it be done? As indicated earlier in this paper, in all other fields of science nearly every triumph has been attained in the face of downright opposition. The way must be found to reconcile the conflicts arising from joint occupation of the national parks by men and animals without impairment of any major park value.

Click below for a Quizlet guide to this essay:

https://quizlet.com/861085732/george-melendez-wright-1-flash-cards/?i=28nu4&x=1qqt

MEN AND MAMMALS IN JOINT OCCUPATION OF NATIONAL PARKS

By GEORGE M. WRIGHT

Joint occupation of national parks by animal and human populations is prescribed by the organic laws which define national parks. Maintenance of wildlife in the primitive state is also inherent in the national-park concept. The conclusion is undeniable that failure to maintain the natural status of national parks fauna in spite of the presence of large numbers of visitors would also be failure of the whole national parks idea.

Further, since the feasibility of preserving the aggregate of primitive wildlife on unit areas anywhere in the United States has become the center of debate between constructive idealists and vociferous defeatists, the national parks, because they represent the problem in its most complex form, have become the test case.

Today, when so much attention centers on conservation based on land classification and the development of management practices designed to restore each class of land to its fullest wildlife productivity, it will be worth while to review the problems which have developed in maintaining the fauna of the national parks in a primitive state, with particular reference to those that are peculiar to them as against other kinds of wilderness reservations.

Stress on Fauna in the Parks: Three Basic Types

Summary: Park fauna struggle with historical impacts, ecological isolation, and human encroachment. Human-related problems are often irreversible, but some problems are fixable. Solutions include species reintroduction, habitat restoration, and managing overpopulated wildlife, alongside expanding parks and planning land use for wildlife restoration.

Though no categorical distinctions can be made between types of problems since there are interactions throughout and indirect influences hardly guessed at as yet, still it is evident that park faunal problems arise from one or more of three basic causes. These are: First, adverse early influences which operated unchecked in the pre-park period, and continued into the early formative period; second, the failure of parks as independent biotic units by virtue of boundary and size limitations; and, third, the injection of man and his activities into the native animal environments.

The first two are common to all areas wherein it is desired to maintain the primitive. Moreover, they have this in common, that we may look forward hopefully to the correction in large measure of the problems which they developed. Consider, for example, some of the type problems under these two causes. As the results of adverse earlier influences, there are problems in the reintroduction of extirpated species, restoration of species reduced to the danger point, rehabilitation of depleted habitats, and management of species become abnormally abundant because of removal of their normal controls. As the results of the failure of the parks to be self-contained, self-walled biological units, typical maladjustments are lack of winter range, ebb-flow of animals that are blacklisted outside the park areas, invasion by exotics, dilution of native species through hybridization, and exposure of natives to the diseases and influences of alien faunas. All the problems mentioned and others referable to the same two causes are recognizable as being common to primitive areas generally. Ideally one can hope that actual cures will be effected as these problems are analyzed and effective treatment evolved and applied.

The third class of problems, however—those arising out of joint occupation of the areas by men and mammals—has the dubious distinction of being the incurable. In the instance of adverse earlier influences the cause of disorder was removed when the area became effectively a national park. It only remains to undo now the damage that was done before. Where the park is an adequate biotic unit, addition of the proper areas and revamping of boundaries to follow natural faunal barriers will bring permanent removal of the basic difficulty. Progress on this front has been slow, but the adoption of a sound Nation-wide wildlife restoration plan based on planned land use should give it a great impetus.

The presence of people, and in fact of as many people as wish to come to the park, is a condition which cannot be altered; therefore the problems arising therefrom are to be dealt with as something permanent. They demand the development of a compensation technique in wildlife administration which will be put into effect and act continuously. Moreover, as park travel is steadily increasing, the problems are being constantly intensified, and it logically follows that the palliative measures including the restrictions willingly imposed on man by himself must also increase.

Though white man is in one sense part of the whole natural environment, one in the aggregate of faunal and floral species constituting the biota of the park, just as are the Indians who came via the Aleutians, and the grasses whose seeds were borne across the ocean, there are two things which set him apart even from other recent arrivals. White man’s impact upon his environment is tremendous as compared to that of all other living forms. He is as much like them as cancerous growth is like normal growth and as destructive in effect. The second thing which sets him apart and which is antidote to the first, is his unique ability to appreciate his effect on his environment. He thus becomes capable of self-imposed restrictions to preserve other species against himself. Admittedly, his object is a selfish one, just as it is when he chooses to destroy other species to use them for food, but it is a higher, more altruistic, selfishness. It is selfishness for the benefit of all individuals of his own kind and their descendents after them. And incidentally it is a selfishness which reacts beneficially upon the animals over which he holds power of destruction.

The whole national park idea is a manifestation of this second attribute of man, dependent upon his utilization of his environment to his own advantage but in contradistinction to his instinctively normal utilization of land. Within the national parks, man’s estimate of the greatest values to be obtained for himself from the sum total of their native resources, dictates that he shall occupy them in such a way as to cause the minimum of modification from the aspect they presented when he first saw them.

Man, like any other exotic, cannot intrude upon an area without causing some displacement and modification of the preexistent or primitive state, but the degree of change which he causes may be very great or relatively little. If a scientific study is made to determine how to keep the disturbances to a minimum, satisfactory results will be secured.

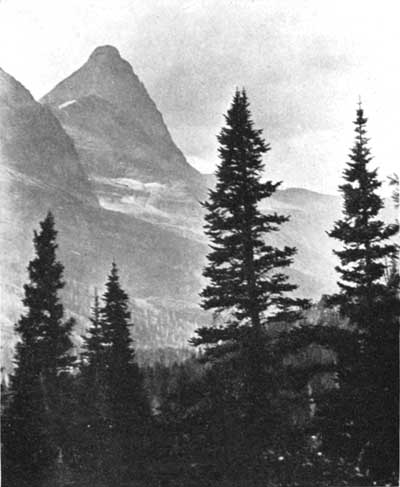

Figure 5. – The whole national park idea is a manifestation of . . . man, dependent upon his utilization of his environment to his own advantage but in contra-distinction to . . .

(Photograph taken September 2, 1931, at Iceberg Lake, Glacier. Widlife Division No. 1875.)

Figure 6. – . . . his instinctively normal utilization of land.

(Photograph taken April 22, 1934, Olympic Peninsula, Washington. Wildlife Division.)

Let us examine those problems already known to be traceable to joint occupancy and indicate still others which may be expected. What has been done to study them and provide for their solution and what is planned by the National Park Service for the future?

Problems Occasioned by “Joint Occupancy” of the Parks by Animals and Humans

Summary: This section highlights the challenges posed by human-animal coexistence in national parks, including wildlife protection, animal-induced human and property harm, and animal displacement by development. It stresses the importance of resolving these issues without harming wildlife and advocates a natural wildlife experience for visitors.

First come those problems rooted in conflict between the more fundamental needs of men and animals in the parks. They are essentially by-products of occupation of common habitats.

In the early park period, the livestock concept of wildlife administration prevailed. Predators were controlled, and rangers were permitted to trap fur bearers in winter to eke out inadequate salaries. This is not to be condemned either, for it was consistent with the national parks concept in that early stage of its development. Moreover, at that time, many of the grazing animals were so depleted that first attention had to be given to saving the small breeding remnants. Some of them, such as buffalo, elk, and antelope, were so close to extinction that any action to save them was justifiable. Now that these forms are out of immediate danger with many nuclei established, it is easy to forget that this was not always so. Then, one spoke of campaigning against carnivores as though they were something devilish, just as one did of Huns in the World War and with as little reason. In fact, it was only a few years ago that the principle of equal protection for all species was established.

Even from their incipiency the parks recognized that the animal life would have to be protected against certain normal aggressions of civilization. Visitors must not molest the animals. Visitors must not bring dogs or, at the very least, they must be kept on leash. Domestic stock must not be pastured in the park by residents, though this was never considered to apply to riding horses.

Such simple precautions seemed enough when parks travel was light and we still labored under the illusion that there were great hidden wildernesses in the West. Later the almost complete decimation of primitive wildlife elsewhere greatly enhanced the importance of the parks as last refuges at the same time that the influx of thousands of visitors raised the question as to whether the park wildlife could stand the pressure. For the first time we began to glimpse the multitude of ways in which the animal and human elements conflicted.

Realization of the problem meant the elimination of the needless harm to animal life which was attendant upon poisoning around barns, burning of meadows, and so on. Maladjustments of this type which are in the accidental class are now corrected as fast as apprehended. They are not the permanent problems in joint occupation.

Once all species are given full protection insofar as the right to live their life cycles unmolested is concerned, and park visitors are at the same time enjoined against taking any step as individuals to protect themselves against the animals, problems in animal harmfulness to man arise. Few species are actually dangerous to human life, but some are injurious to property, others to man’s special interest in certain natural features of the park, while still others are inimical to his comfort and esthetic senses.

The rattlesnake is, of course, a traditional enemy but, nevertheless, a greatly overestimated one. The proper practice is to destroy rattlesnakes when encountered at human concentration points but to permit them to go unmolested elsewhere.

Coyotes, rabbits, and squirrels may act as carriers of diseases communicable to man. Epidemic outbreaks of such diseases constitute emergencies abrogating all regular rules and regulations and calling for heroic but temporary and specifically applied local treatment.

Among mammals, the various species of bears can be considered as being physically dangerous. Because visitors cannot carry fire arms, this danger is real, and if the park administration protects the bears against the visitors it must protect the visitors against the bears. For this reason, individual bears of bad character are destroyed. But the bear problem is due very nearly 100 percent to the abnormally intimate contacts which human beings have sought to establish with the bears and not to the innate ferocity in bear nature. The subject, therefore, is properly referable to that category of problems involved in the manner of presentation of the visitors to the wildlife and will be treated later.

Mammal damage to property is of small significance. Since the offenders are not to be destroyed, recourse must be had to isolating the property from the animals. The real difficulty here comes in inculcating the basic administrative policies so deeply that recourse to this kind of treatment will always be first thought, replacing the instinctive reaction to kill. For example, in Mount McKinley National Park considerable damage is sustained from the porcupine gnawing on buildings. The immediate proposal was local control by shooting. But such an objectionable course was unnecessary. Moreover, since the porcupines of this region migrate locally, serious reduction of the park porcupine population could result from prolonged application of such treatment. At present, the offending porcupines are trapped and moved elsewhere. In all likelihood, a permanent solution to this problem will be found through cooperation with the Branch of Plans and Design of the National Park Service in development of an acceptable porcupine-proofing. This then will become standard for all structures where such damage occurs.

Cases in which animals prejudice the comfort of the visitor or abuse his esthetic senses demand the development of similar technique. Where skunks insisted on sharing man’s houses with him, they were once trapped and drowned. Now they are trapped and removed to remote sections. It is a safe prediction that skunk-proof basements will be standard in the future.

Where animals prejudice man’s special interests in the natural features of the parks, the involvements are greater. The scene of man’s special interests is out in the park proper and more often than not in the most sacred areas, whereas the troubles discussed above are usually limited to the development areas, which are exceptions from the remainder of the park area in nearly every way.

If a park has been created for the express purpose of preserving an outstanding archeological object, the welfare of that object, including both protection against destruction and presentation in a primitive setting, transcends all other administrative obligations, including that of wildlife protection. Thus, if a hard-hoofed species is hastening the destruction of a ruin, or a rodent is destroying vegetation which is an important part of the ruin picture, there can be no question of tolerating the damage, and the offender must be extirpated from the immediate locality if no other and less objectionable solution can be found. Fencing, for example, would intrude an artificial element in the ruin scene and therefore would be eliminated as a possibility.

The inroad of fish-eating mammals upon game fish is detrimental to the special interests of one group of visitors. Nor can we be oblivious to the perfectly understandable hostility of the fish culturist whose business it is to keep the park streams well-stocked. But the logic of the arguments that the fisherman is a privileged character in a national park wherein nothing else but fish can be taken; that, in so doing, he is depriving the fish-eaters of their food supply; and that he must restore fish to the streams and lakes for the benefit of these creatures as well as himself, has been so forcefully demonstrated, that there is no longer any question of controlling species predatory upon fish. For purposes of practical administration exceptions have to be made in the case of individual animals, doing unusual damage around rearing ponds or hatcheries.

Finally, since man is superior, and endowed with every advantage, it would be miserable admission of defeat if he could not find ways of solving these simple problems of animal injury to man without resorting to campaigns of destruction which ruin the primitive and impoverish the aggregate of natural phenomena which, in reality, is the park.

In turning to a consideration of maladjustments of the reverse order, those involved in the repercussions of civilization upon the wild mammals both by direct effect and indirectly by disturbance of environments, we come to grips with the key problems in national parks administration.

Consider first the unavoidable factor of actual physical displacement. All construction projects today must conform to the master plans which specifically limit developments to certain excepted areas. The guiding principle is that all the roads and buildings necessary to the accommodation of both permanent employees and transients shall be compacted into the smallest possible space. Though this technique is in its infancy, rapid progress is being made. Approved practice today often calls for erection of apartment-type dwellings to secure economy of ground space.

For better control and to accord with the most advanced scientific thought on the subject, the research reserves program developed by the Ecological Society of America has been adapted to national parks use under a plan proposed by the Wildlife Division of the National Park Service. Under this scheme the whole of the park becomes a primitive area with the exception of certain fixed and well-defined areas to which developments must be limited. The excepted areas include right-of-way for roads and site for camps, hotels, and utility groups. The primitive area, which is the park proper, must remain untouched except for fish culture, trail development, and insect and fire control practices. For scientific study and to serve as control experiments, specific areas within the primitive area may be set aside as permanent or temporary research areas. In these, fish planting is prohibited. To make this program satisfactorily effective, the park should be surrounded by a buffer strip of the maximum width possible, in order to isolate it from external influences. Success of this measure must depend on whether adjacent lands are in public or private ownership and on the degree of cooperation which can be secured.

Adoption of this plan will mean reduction of the displacement factor to the practical minimum. In order that neither enjoyment and use of the park nor the primitive status of its wildlife shall be jeopardized, men must live on less and less ground and do more and more journeying forth to see the wildlife. There is ever-increasing restriction on the camping privilege. Before long, no one will camp in the park except in a developed camp site in which the location of car stall, fireplace, table, and tent have all been predetermined by the Branch of Plans and Design. Though such a degree of seeming restriction upon freedom is naturally abhorrent, the parks are our most precious bits of wilderness and must be safeguarded. The vast areas outside the parks provide ample space for those who would camp as they please.

In addition to the impingement by large numbers of people upon the faunal habitats, causing a contraction in the total animal populations, there are certain corollary maladjustments which develop. In all of the national parks every bit of available range forage is needed for native game. Both company and Government saddle horses have been given the range needed by the park wild animals for so long that the practice is rooted in tradition and is hard to change. Nor can it ever be eliminated entirely. Nevertheless, a great improvement has been effected by maintaining careful jurisdiction and exercising good range management. Riding horses maintained in the park for visitor use are not brought in until the season starts and are taken out of the park as soon as it is over. Numbers are limited to the demand. And what is more beneficial than anything else, the horses are herded high upon the summer range instead of being allowed to impoverish the critical winter game range.

A few species of mammals which thrive on civilization, notably coyote and ground squirrel, tend to increase and spread in the wake of development and, by very virtue of their aggressive characteristics, to impinge upon native forms whose niches they preempt. In such cases, control is clearly indicated. In parks such as Glacier and Yellowstone, however, the coyote, while it is undoubtedly more abundant then formerly, may perform a useful function as a salutary control on herbivorous forms in place of the mountain lion and wolf, which formerly filled that role.

Finally, among the problems of joint occupation, there is the large and complex category of problems involved in the manner of presentation of wildlife to the visitor. That there are such problems is due indeed to the very perversion of what should be the relationship between the animals and the visitors. The visitor, instead of seeing animals disjoined from their natural habits and drawn out of their natural haunts to be presented spectacularly to him on as intimate terms as possible and with the minimum expenditure of energy on his part, should in fact be presented to the animals, so as to see them at home behaving primitively in their primitive environments.

Figure 7. – As it should not be – animals disjoined from their natural habitats and drawn out of their natural haunts to be presented spectacularly . . .

(Photograph taken November 2, 1929, at Yosemite. Wildlife Division No. 935.)

Probably the most typical and certainly the best known problem resulting from the manner of presentation is that of bears in Yellowstone. To show how this problem was analyzed and what progress has been made toward its solution, the following excerpts are quoted from Fauna of the National Parks of the United States, Volume I, published in May 1932, by the National Park Service:

Pitfalls of Animal Presentation: Feeding the Bears

Summary: Providing bears with excessive garbage in parks results in disease spread, altered diets causing physiological issues, natural food shortages, older bears dominating younger ones, disrupted ecosystem interactions, and more human contact, fostering negative views of bears, ultimately harming their well-being.

The manner of presentation of bears in this and other parks has been to feed large quantities of garbage in arenas, there being one or more of those according to the distribution of human population centers. This has brought about unprecedented concentration of bears in small areas in Yellowstone. What are some of the adverse or possible adverse effects upon the bears resulting from this manner of presentation?

(a) The intimate association of many bears at one time on the feeding grounds must facilitate the spread of diseases or parasites which may be endemic in bears in Yellowstone, or of any diseases which may be introduced among them.

(b) The garbage itself, including the remains of domesticated animals, may introduce parasites.

(c) The rich concentrates in the garbage are an unnatural food for bears; and if feeding of them is continued for many bear generations, injurious physiological changes in the make-up of the bears are exceedingly likely to occur.

(d) The garbage season is coincident with the tourist season and not with the bear requirements. As a result of this uneven distribution of food, there is likely to be a scarcity of feed at the critical times. If it is true that because of this unnatural condition the females go into hibernation in a poor condition, there is a genuine possibility that the cubs born in the winter months will suffer until eventually degeneration of the race will take place as a result.

(e) Inasmuch as the garbage is concentrated in areas a few yards square, the old bears are able to dominate the situation at the expense of the younger animals. It is possible, on the other hand, that the young animals learn only the feeding habits of their elders; and not being trained to rustle their natural foods, become the small, scrawny, hold-up bears so common on the Yellowstone roads.

(f) The garbage pits must cause a desertion of the niche formerly occupied by the bears in the summer time, thus further disturbing normal biotic relationships in the park.

(g) Garbage feeding attracts the bears to the vicinities of the food stores of campers and encourages a lack of fear of man. The bears offend man, who has the whip hand, so that the bears are bound to be the sufferers in the end.

(i) Bears appear at their worst on the garbage platform, so that their characters, in the minds of the visitors, suffer as well as does very probably their physical well-being from this manner of presentation.

To conclude, it might be said that this manner of presentation of bears is very likely to be to the ultimate detriment of the bears. Certainly it is responsible for much of the injury to man.

In the two seasons which have elapsed since this analysis of the Yellowstone bear problem, certain corrective steps have been taken, and there is immeasurable improvement. Garbage feeding has been eliminated except for the Canyon and Old Faithful bear shows. Back-door feeding of bears and feeding of bears by visitors has been greatly reduced and eventually will be completely eliminated. Approximately 100 troublesome black bears and a very few bad-actor grizzlies have been destroyed. The number of bear complaints reported in the 1933 season was about 60 percent less than for the preceding year. For 1934 an allotment for bear-proof refuse containers and food safes has been secured for one campground. If this experiment proves successful, all campgrounds will be bear-proofed as fast as funds can be made available.

Not only with bears in Yellowstone but wherever any animal has been garbage-fed, hand-fed, petted, and tamed, the results have been detrimental both to the animal and to man in the park. Moreover, such practices have no national parks value, since the city zoo can satisfy this sort of human craving far more successfully. If we do not present park animals wild and in their natural background, we do not present a wildlife picture of national parks significance.

In arranging for the presentation of the visitor to wildlife it must be remembered that birds and mammals in the immediate vicinities of roads and development areas are of relatively greater value because they are the ones which are most apt to be seen. Roadside clean-up tends to make the part of the park seen by visitors sterile of wildlife. Therefore it should be kept to the absolute minimum. Office orders urging caution to preserve wildlife values in conduct of Emergency Conservation programs have been issued, and close supervision is exercised. Still it is difficult successfully to combat human zeal in making the woods as tidy as possible.

The general recommendations calculated to secure the best values to the visitor from park wildlife and at the same time to avoid destruction of the primitive status of that wildlife are that the wilderness be permitted to come up as close as possible to human concentration areas, that park animals be not pauperized or tamed, and that ingenuity be exercised to introduce visitors to the animals’ environments without their presence having adverse effects.

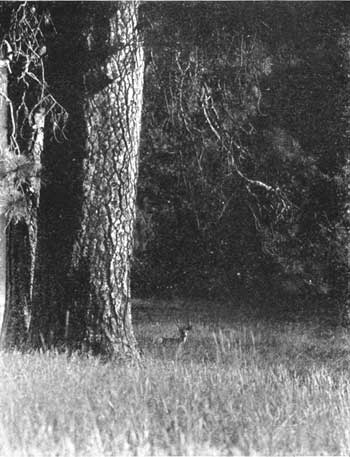

Figure 8. – If we do not present park animals wild in their natural background . . .

(Photograph taken July 13, 1929, Yosemite. Wildlife Division No. 67.)

Figure 9. – . . . we do not present a wildlife picture of national parks significance.

(Photograph taken April 27, 1932, Mammoth Hot Springs, Yellowstone. Wildlife Division No. 2519.)

Recapitulation

Summary: There is a critical need to balance human activity with the conservation of wildlife and natural conditions in national parks. This final section acknowledges the challenges in maintaining this equilibrium but stresses its importance for the well-being of civilization.

This country has now been explored and occupied from coast to coast and from Canadian to Mexican boundaries. The haphazard development and cropping of natural resources has proved so enormously wasteful and unproductive of benefit to our citizenry that the future national welfare in this respect has been seriously threatened.

Under a reclassification of lands to secure the maximum benefit from each type, wildlife will find some place everywhere. The percentage value accorded to wildlife may be very small in some cases, but it will be considerable for most lands and on some, such as marsh, desert, and rugged mountain types, wildlife values will out rank all others.

Conservation thus is seen to be not an end in itself or a creed over which men fight according to personal prejudice, but a means for securing the maximum cropping of natural resources without destruction of the productive capital. The forms of cropping include the realization of sporting, economic, esthetic, and scientific values.

Certain areas in public ownership will always be dedicated to the preservation of wildlife in the wilderness condition. Because the modifying influences exerted by human populations would ordinarily prevent the realization of this objective, administrative practices must be developed to correct and prevent modification of the original natural conditions.

The national parks are one among the various types of areas which are designated for the preservation of the primitive. Because the parks are set aside both for preservation of natural conditions and for use by the people at large, they have not only to cope with problems resulting from adverse influences and problems of adverse external influences, but they are confronted also with the problems resulting from joint occupation.

These problems are of such magnitude that some observers have concluded that only the childish idealist, pathetically blind to the practical obstacles, would attempt to accomplish the thing. There are others who believe the effort is warranted. Much of man’s genuine progress is dependent upon the degree to which he is capable of this sort of control. If we destroy nature blindly, it is a boomerang which will be our undoing.

Consecration to the task of adjusting ourselves to natural environment so that we secure the best values from nature without destroying it is not useless idealism; it is good hygiene for civilization.

In this lies the true portent of this national parks effort. Fifty years from now we shall still be wrestling with the problems of joint occupation of national parks by men and mammals, but it is reasonable to predict that we shall have mastered some of the simplest maladjustments. It is far better to pursue such a course though success be but partial than to relax in despair and allow the destructive forces to operate unchecked.

(Read May 8, 1934, at the Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the American Society of Mammalogists, American Museum of Natural History, New York City.)

Click below for a Quizlet guide to this essay:

https://quizlet.com/865846940/george-melendez-wright-fauna-pt-2-flash-cards/?i=28nu4&x=1qqt

THE PRIMITIVE PERSISTS IN BIRD LIFE

OF YELLOWSTONE PARK

By GEORGE M. WRIGHT

Days with the birds in Yellowstone are tonic to him whose spirit is bruised by reiteration of the lament that wilderness is a dying gladiator. Too frequent exposure to a belief born of despair is not good for any man. To conservation, it is a poison the more deadly because the injurious effects remain unnoticed until a lethal quantity has accumulated in the system.

There is an obvious prevalence of the conviction that perpetuation of primitive wildlife anywhere on this continent is impossible in face of the expansion and intensification of European-type civilization. Neither is it to be denied that this particular defeatism has been a boon to the greedy one who would justify his seizure of the last egg or his eating of the last duck.

Honest recognition of all factors operating to destroy the wilderness and of the amount and rate of such destruction is nothing to decry. Propaganda from this source is salutary if accompanied by proper advertisement of the facts, and providing that it is presented as diagnosis with prescription for treatment and not intoned as a funeral oration.

Changing a Jaundiced Outlook: Efforts to Keep Nature Natural

Summary: Efforts to conserve primitive wildlife in national parks and forests have faced various challenges, but they have ultimately been successful in restoring and preserving natural habitats. These endeavors have evolved over time to adapt to changing conditions and ensure the continued protection of wildlife areas.

The national parks and national monuments and certain designated areas within national forests have constituted the strong line of defense in the conscious determination to preserve representative examples of the primitive wildlife of America. In the beginning we were blithely unaware of the complexities involved in this undertaking, unaware that acts of Congress and ranger patrols were but preambles to the real task of keeping nature natural. The first sharp pain of awakening inducted a sore travail, the taking of inventory to determine the adverse influences, their causes and their effects. From this labor a new principle was born. Henceforth, scientific, planned management would be used to perpetuate and restore primitive wildlife conditions. The earlier protect-and-hands-off policy had abundantly shown it could not accomplish this objective alone and unaided.

Even before the birth a spectral wolf haunted the scene. Ever bolder, his howls now make the night one long anxiety, for he shouts to heaven that the baby lives in vain. Small wonder if the nurses whose duty it is to appreciate every hazard over which their charge must triumph and to prepare him for it, now and then grow discouraged. Their heavy task becomes quite unbearable with that added tribulation, the defeatist headshaking of the spectral wolf.

Often it is but a small unnoticed shade of change which transforms the pleasant task into burdensome duty. I do not know when the change occurred, but there came a day when the elk bull standing on a much-too-near horizon was no longer the embodiment of wild beauty, no longer a wild animal at all to me, but just next winter’s great big problem, a dejected dumb brute leaning on the feed ground, its gums aflame with foxtails and suffering from necrotic stomatitis.

It was the fear of fixation in this jaundiced outlook which first suggested a changed diet through study of the healthy elements in the picture instead of so much concentration on the bad spots. The refreshing mental exercise of analyzing observed incidents for their faithfulness to primitive life brought me to these reminiscences of a few among the many hours spent watching the lives of birds in Yellowstone.

The Yellowstone-Teton area, roughly speaking, a plateau some one hundred and twenty miles long by sixty wide, of altitude varying from six to eight thousand feet, and encircled by mountains rising from three to six thousand feet above its plain, was one of the wildernesses late in yielding to man’s violation. Though the three largest rivers of the country, first roads of exploration, clawed thirstingly at the flanks of the Gallatins, Absarokas, Wind Rivers, Hobacks, and Tetons, the ruggedness of these ranges and their long lingering snows discouraged all but the hardiest scouts like John Colter and Jim Bridger.

In the course of time even this land was called upon to yield much from its rich stores of game and fur. The trappers who went in came out laden, yet they told little, as it was not their way incautiously to brag about the best trapping grounds. The game beyond the mountains was nearly annihilated, and much of this was the same game that had summered in luxury on the abundant grasses of the plateau. Then the dude explorers and hunters — “Muggses” they were called in their day — came to take a share. Protection was only a name in the first years after the park was set aside, and very probably less than that insofar as the game was concerned. Finally, the automobiles, shrieking over fast roads, brought thousands of well-meaning but thoughtless visitors whose very presence would seem paradoxical to the concept of wilderness.

In spite of all these vicissitudes, each one of them a fearful impact on the primitive, today the beavers are back by the hundreds, content in the freedom to pursue their inherent way of life, without ever a lurking fear that they might be born to ride to the Paris opera astride some dandy’s eyebrows as did their beaver forefathers not so many beaver generations gone by. Down in the Bechler swamps, the lone loon is as solitary as the poet’s version would be pleased to have it. Shiras moose thresh the willows in Willow Park, their behavior so naturally easy that the wide-eyed tourist might well wonder if it is not himself who is exotic in these surroundings and therefore the curious object. While watching a marten in the woods of Heart River, a coyote amongst the ghost trees of Middle Geyser Basin, a badger on the boulder-strewn hills of Lamar Valley, I have sometimes felt almost offended by the suspiciously elaborate disregard of my presence manifest in their behavior.

Yellowstone Birds: Persistence of the Primitive

Summary: In Yellowstone, diverse bird species flourish, showcasing nature’s tenacity amidst human encroachment. These birds’ behaviors and their engagement with the environment are closely observed. Efforts to preserve the park’s primitive character have led to protective measures. This proactive stance helps ensure the continued presence of Yellowstone’s avian population, highlighting the balance between conservation and recreation in one of America’s most iconic natural landscapes.

But it is the birds of the water, beautifully wild birds by the thousand, that are encouragement and inspiration to the man who prays for conviction that the wilderness still lives, will always live. The shimmering silver sweep of the many lakes large and small, and the calm yellow-brown expanse of the broad, warm rivers harbor a varied and abundant bird populace. Trumpeter swan, sandhill crane, white pelican, Canada goose, American merganser, mallard, Barrow golden-eye, California gull, and osprey are outstanding in the picture, some because they are large birds, others because there are so many of them. In the case of the Canada goose it is both. Cormorant, Caspian tern, loon, Harlequin duck, willet, avocet, solitary sandpiper, shoveller, sora rail, great blue heron, and others earn distinction on a day’s list because they are either rare or rarely seen. And the red-letter, wood-ibis day may not repeat itself in one person’s experience. Other birds of more usual occurrence are coot (myriads of these), ruddy duck, pintail, green-winged teal, blue-winged teal, scaup, eared grebe, pied-billed grebe, buffle-head, red-winged blackbird, yellow-headed blackbird, belted kingfisher, western yellow-throat, tule wren, Wilson snipe, Wilson phalarope, and the inland waters’ constant companions, dipper, killdeer, and spotted sandpiper; and beyond all these, fully again as many more.

The concentration of so many waterfowl so high in the mountains is in itself an amazing thing. The readily apparent cause of this unusual spectacle is the abundance of warm shallow waters in both the streams and lakes which favor production of the preferred foods.

Sometimes while I am watching these birds on the water, the illusion of the untouchability of this wilderness becomes so strong that it is stronger than reality, and the polished roadway becomes the illusion, the mirage that has no substance. The impression of the persistence of the primitive is strongest in those exciting minutes when the birds are observed struggling to outwit their natural enemies or in a competition against one another, themselves oblivious to all but the primeval urge of the moment.

The notebook records many interesting incidents in the natural lives of Yellowstone birds, some of them particularly suggestive of the theory that animals hew closely to the way of life peculiar to their species, ignoring man-made changes in their environment so long as these do not constitute insuperable obstacles demanding deflection of habit.

Figure 10. – Canada geese frequent the roadside meadows – often as if no road were there.

(Photograph taken September 10, 1929, at Twin Lakes, Yellowstone. Wildlife Division No. 387.)

Among Yellowstone birds, the sandhill crane is reputedly the wariest. Its bearing is always patrician. For all that the swan is a tradition of grace and dignity, still the familiarity that breeds contempt brings a day when one is close to confessing this bird’s kinship to certain inmates of Si Farmer’s duckpond. The sandhill crane never gives a chance for familiarity. In its aloofness there seems to be more than fear. A first acquaintance made in 1930 left an impression that subsequent events have failed to erase. It seemed as if the cranes eschewed close association of any sort with the whites who had come to trespass upon their chosen solitude. Only with the dire need to protect their young did the barrier break down.

In early June 1931 we stood on the edge of a lost, lily pad lake in the Bechler River district. The gleam of sunlight on a rusty red head pressed closely down revealed a sitting crane. Though we halted in our tracks and made no movement, she could not endure our presence for more than a couple of minutes. I could not tell afterwards how she rose from the nest, but there she went, crossing the lake with slow, sweeping steady wingbeats, uttering that strange unearthly call which is the very embodiment of all wildernesses. Slowly she lifted, gaining just enough altitude by the time she reached the lake’s far shore to clear the lodgepoles and disappear from our view. There were two eggs well advanced in incubation on the flat raft of tule stems.

In 1932, this time on the last day of July, while we were riding across a wet meadow near Tern Lake, two sandhill cranes permitted us to come much closer than usual. The explanation was right under foot. Our horses jumped aside as a half-grown baby exploded from the young lodgepoles and went careening out across the uneven ground. We tried to run down this grayish-pink fledgling, but our horses were at a disadvantage, and once it reached the forest on the other side our quarry disappeared like magic. The one parent that remained on the scene flew from one hillock to another in silence. In alighting it would come in on a long slant, lightly touch its feet to earth in twelve to fifteen giant paces, and finally come to rest with wings folded.

We had always maintained that this was one bird which would never consent to abide with man, but the summer of 1933 proved us wrong. All through the season two pairs of cranes each with a single young, fed unperturbedly in the meadows north of Fountain Geyser in full view of the constant procession of cars. On September 13, when last observed, the youngsters equaled their parents for size, though readily distinguishable by the reddish-brown streakiness of their bodies and the lack of color in the head markings. That same day we located a third family with two juveniles not more than a mile airline from the other two. It was a gala day indeed, for we felt that it marked Yellowstone’s high achievement in perpetuating the primitive in the presence of man.

An early morning in June found us driving from Canyon to Lake, a route which is always interesting because it never fails to reveal a fascinating wildlife panorama. Where the road closely parallels the Yellowstone River, two American mergansers were acting strangely. Both wore the gaudy trappings that proclaimed their maleness to the whole world. The foreparts of one merganser were thrust under water. Its tail was elevated, and the wings were slightly spread as with some extraordinary effort. The other merganser fussed alongside. Presently the struggles of the first ceased, and both of them began to circle excitedly around and around over the spot. A California gull came out of the nowhere, swooping past with a ghoulish cry. Back again it swung, then most unexpectedly departed in screaming, precipitate retreat. Before we could cogitate the unorthodoxy of such an ungull-like act, the mergansers, too, were lost to sight under the spread of a white fan-tail and the beating of broad dark wings. From a sparkle of spray, a bald eagle rose with one 10-inch native trout. And now the story was plain. The mergansers had tackled a trout too big to be managed. The gull foraging up the river sensed the possibility of a steal, only a few seconds before the swift approach of the eagle changed lust to fear. There we were, all of us, too much startled by the sudden dive of the great bird to do much of anything at all. With measured strokes the monarch winged away toward the distant wooded bench where, it is rumored, it occupies the same nest from year to year.

A pair of Harlequin ducks dropping down through the fast water below the Cascades was the second touch of the unexpected. In the bright morning light the rich red side of the male was the conspicuous identifying mark, the more bizarre paintings on head and neck not being revealed at a distance.

In a marshy expanse of the river not far from Mud Volcano, a pair of trumpeter swans were quietly feeding, and when we returned that way late in the afternoon they were still there, a picture of perfect repose in the soft caress of the setting sun. Though we never left the car in making these observations, what we saw was all wilderness life.

The story of the white pelican is a sorry one the country over. California, for instance, which once had at least nine colonies and 2 years ago could still boast one, failed to produce any young in the summer of 1933 because of drought. But the wilderness of the Yellowstone fights to protect its own.

The presence of white pelicans on Yellowstone Lake has been continuously recorded for over 50 years, and it is safe to assume that they have bred there for a long, long time. Rumors, probably well founded, since the antipathy of fishermen against all the fish-eating birds and mammals is well known, tell of numerous raids on the breeding islands, and the control experiments which were officially sanctioned are a matter of record. Today the fish predators in national parks have equal rights with all other classes of animals.

There is written into the Park Service code for wildlife the following policy:

Species predatory upon fish shall be allowed to continue in normal numbers and to share normally in the benefits of fish culture.

In spite of the pressure to destroy the primitive which was brought to bear before this permanent peace was signed, the colony seems to have maintained a fairly constant status throughout. Each year has revealed the same sort of domestic activity down on the island nursery.

The general sequence of events, together with species noted and the numbers of each, have all been so constant for each of the trips we have made that the chronicle of any one of these excursions will do as a pattern of the rest. This particular trip took place on June 4, 1932.

The Bureau of Fisheries’ boat makes a broad furrow for 18 miles up the lake before the tiny Molly Islands at the head of the southeast arm are sighted. A hazy cloud of gulls first marks the spot for us. Then a half hundred pelicans rise up among them. For a few minutes they whirl about in disorder, then organize the flying march which takes them over to a sandspit on the mainland where they alight and remain, still in the order of march, at rest but watchful. While the boat is still a hundred yards off shore, two cormorants shoot out across the water straight and low like two torpedoes leaving a destroyer. At the same instant the calls of startled Canada geese come to us from the far side of the islands. Later someone spies the geese heading for the marshes at the river mouth.

While we are coming to anchor and casting off the rowboat the cloud of gulls thickens and their protests shatter the calm. Among them are two Caspian terns, but they are not so fearless as the gulls, and soon are lost from the picture. Not until our boat scrapes on the pebbles do the sitting pelicans decide to abandon their nests to the enemy. We scramble to high ground in time to see the last reluctant three take to the air.

The Caspian terns are presumed to be breeders, but this year as before we fail to find their nest among the 564 which we count as belonging to the California gulls. We find the single cormorant nest with 3 eggs. The cormorant population seems to remain constant at 1 pair. The 9 goose nests on the 2 islands contain a total of 19 eggs, 5 being the largest number in 1 nest. There are 126 occupied pelican nests, and 232 eggs. Three nests contain 4 eggs each. Two western willets, a few Wilson phalaropes, and the usual complement of spotted sandpipers complete the Molly Island census for the day. We hunt in vain for a blue-winged teal nest, remembering well the one we found on Pelican Island in 1930.

The year 1932 marked a milestone in the Yellowstone white pelican saga. That year, respect for the pelicans reached the point where the superintendent of the park issued an order prohibiting all boats from even passing close to the Molly Islands during the nesting season, the only exceptions to be two or three ranger-conducted surveys for census purposes. Persistence of the primitive in the face of much interference has won its reward, another victory for wilderness.

Figure 11. – Far down in the southeast arm of Yellowstone Lake the two tiny pelican islands lie. Not until our boat scrapes on the Island pebbles do the sitting pelicans decide to abandon their nests.

(Photograph taken June 4, 1932, at Yellowstone Lake, Yellowstone. Wildlife Division No. 2466.)

There is an aura of wildness about the cluster of lakes deep in the wooded heart of Mirror Plateau which stills the voice and quickens the senses. From the first, our experiences in this territory taught us to watch for the unexpected. The trip of June 1932 yielded no particular excitement until the moment of our departure on the morning of the 25th. We walked up the crest of the hill on the west side of Tern Lake where we could get a good, though somewhat distant, view of the trumpeter swan nest that we had been studying. Both parent birds were out of sight, so we started on. At the last opening in the trees we hesitated for the fateful last look.

Bird Meddlers: Otters, Scientists, and Others

Summary: During what he calls “field days,” Wright points out that there are other “meddlers” that birds face besides the occasional scientist. Animals such as otters, coyotes, and other birds, pose a risk to some birds’ offspring. He concludes by stating that a better understanding of how animals act in the wild can lead to better management practices.

A black object loomed by the swan nest. With field glasses glued to our eyes, we saw that it was an otter stretching its full length upward to peer down into the nest. From one side it reached out toward the center and pushed aside the material covering the eggs. Then the commotion started. With rapt interest, the otter rooted around in the dry nest material, heaving up here and digging in there, until it was more haystack than nest. Then the otter started to roll, around and around, over and over. This went on for a number of minutes. At frequent intervals its long neck was craned upward, and the serpentlike head rotated around to discover (we supposed) if the swans were returning. At last the otter seemed too weary of this play. It climbed from the nest to the outer edge, then slid off into the water. Swimming along the edge of the marsh grass, it was the undulating silver demon of the water world. Once it dove and several times detoured into channels through the grass, only to come right out again and continue on. It never turned back, and was finally lost to sight.

Where were the swans all the while we had been praying for their return? We well remembered that time 2 years ago when they came flying in from a far corner of the lake to drive off a raven which had already broken one egg. Careful search with the glasses revealed the parents, all that we could see being the water-stained beads and black bills protruding from the marsh grass. One was about 600 feet from the nest, the other not more than 240 feet. Yet both birds gave no evidence of concern. Seeing that the damage was already done, and another year’s potential swan crop for the Mirror Plateau lost irrevocably, we saw no further reason for caution. So we stripped off our clothes and waded out across the shallows. We were amazed to find all five eggs intact. There they were, all together, rolled to one side, but perfectly whole. So much for the circumstantial evidence. Had we gone on, Mr. Otter would have had one order of scrambled trumpeter swan eggs charged on his bill.

We covered the eggs and hurried away in confusion as huge hailstones pelted our bodies. We hoped that the parents would return to protect the eggs from chill. The storm obscured the scene, obliterating the next chapter in the story. Later we learned from the ranger reports that no cygnets were raised on Tern Lake that year. Which meddler should shoulder the blame, the otter or the scientist?

Mirror Plateau has been made a research reserve. The only trails leading in are elk trails. No developed trails will ever find a place there, and of course no roads. Since no trout are ever to be planted in these lakes, there is every reason to hope that here again the fugitive wilderness has found another safe retreat.

The Mirror Plateau, however, like Molly Islands, is a special case. Here man has shut himself out to protect the wilderness. We seek to retell those occurrences when it seems that the wilderness has persisted in its primitive characteristic in spite of artificial developments.

We stood on the road the cold morning of November 10, 1932, watching the sun lift the veil of mist from the meadows at the head of the Madison. Wild fowl floated on the river with that economy of movement so characteristic of wild creatures in cold weather. Men stamp their feet and blow in their hands, but the animals and birds seem to conserve their body warmth to best advantage by staying very still.

The bald eagle usually present in this section in winter made its rounds and disappeared in the direction of the Firehole. A coyote sat out in full view in the middle of the snow-white meadow with a cocky mien which seemed to say that it had done enough mischief of a serious sort during the night and now awaited something to arouse its curiosity. Of course no good scientist would be guilty of even toying with the fancy that a coyote could be suspected of thinking at all. Oblivious to such insult, the coyote presently came trotting toward the river bank and proceeded to go on a still hunt for birds. He worked downstream, keeping back out of sight except where a break in the bank or some protective cover permitted him to come down to the water’s edge. When five Canada geese near the opposite shore caught sight of the enemy they kicked into the air and flew off calling loudly. They broke the sweet silent spell. Mallards and American mergansers seemed aware that their position was impregnable and paid no attention. Nine mallards swam downstream right past the coyote, which by now was openly eying them from the bank. The coyote turned its attention to hunting small rodents in the meadow, and we started up the road. A single Clark nutcracker crossed in front of us.